Atlanta Fed President Bostic Says October Would Be ‘Reasonable’ Time To Begin Tapering Bond Purchases

Image source: Reuters

By Howard Schneider

It would be "reasonable" for the Federal Reserve to trim its bond-buying program beginning in October if strong job gains continue, Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic said in the latest call by a U.S. central banker to start tapering the purchases soon and end them fast.

The Fed has been buying $120 billion in U.S. Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities each month to stem the economic fallout from the coronavirus pandemic, but is now moving toward reducing the stimulus as the recovery gains momentum.

"I would be comfortable with an October timeline for starting this" if U.S. job growth in August matches the nearly one million jobs that were added in each of the previous two months, Bostic told Reuters in an interview published on Friday.

The Fed could announce a plan to "taper" the asset purchases at its Sept. 21-22 policy meeting. A change is expected sometime this year, with debate still unfolding over when the plan should be announced and how fast the purchases should be reduced.

Bostic said that, once the taper started, he was "definitely looking to get this done as quickly as possible," and could support a full end to the Fed's asset purchases "toward the end of Q1" of 2022.

He spoke to Reuters ahead of the Fed's marquee Jackson Hole research conference, which will be kicked off with a speech on Friday by Fed Chair Jerome Powell. Bostic is a voting member of the Fed's policy-setting committee this year, and joins a vocal group of mostly Fed regional bank presidents who are ready to end one of the central bank's signature pandemic programs.

Beyond the taper debate, however, Bostic delved into the Fed's next-phase discussion of when to raise interest rates.

Since early this year he has said he expected inflation to be stronger than expected, and anticipated the Fed will need to lift its benchmark overnight interest rate above the current near-zero level sometime in 2022 – a step towards tempering the economic expansion to ensure prices remain under control. Most of his colleagues don't see rates rising until 2023 or later.

But more fundamental than the timing, Bostic said he felt Fed officials needed to begin to talk more precisely about how their new inflation approach will play out in practice, particularly now that the pace of price increases has run faster, for longer, than expected.

Inflation this year is pushing 4%, and the pace of the price hikes has been so strong this year that it has pushed average U.S. inflation over a period of several years up to the Fed's 2% target.

Under a new approach adopted a year ago, the Fed is focusing on that average figure and will allow high-inflation "overshoots" to help reach it. But the central bank is not explicit on how long the averaging period should run or how much of an overshoot might be tolerated.

"By some metrics that are straightforward we have already met the goal," Bostic said, adding that the Fed will face inevitable questions about what yardstick it will use. "We should be transparent to the marketplace. This is our first round going through this and approaching this benchmark, so I do think there is value in thinking about how to communicate and signal more directly where we think we are."

A second pledge, to get the economy to "maximum employment," is also undefined, but assessments of that will have to be a "game-time decision" for Fed officials weighing the labor market recovery against inflation risks that may emerge, Bostic said.

The Fed has said the job gains should be "broad-based and inclusive," but Bostic said at the same time "there is not a consensus view on a metric" for measuring the completeness of a jobs recovery.

"There is not a clean analogue on the employment side relative to what we have for inflation," he said. If an interest rate hike seems required, but the job recovery seems less than finished among different demographic groups, "policymakers … will have to decide and weigh the risks of forbearance … There is a learning curve to how it is going to play out."

'THE MATH'

For the more imminent decision about the bond-buying taper, however, Bostic said the numbers are starting to add up.

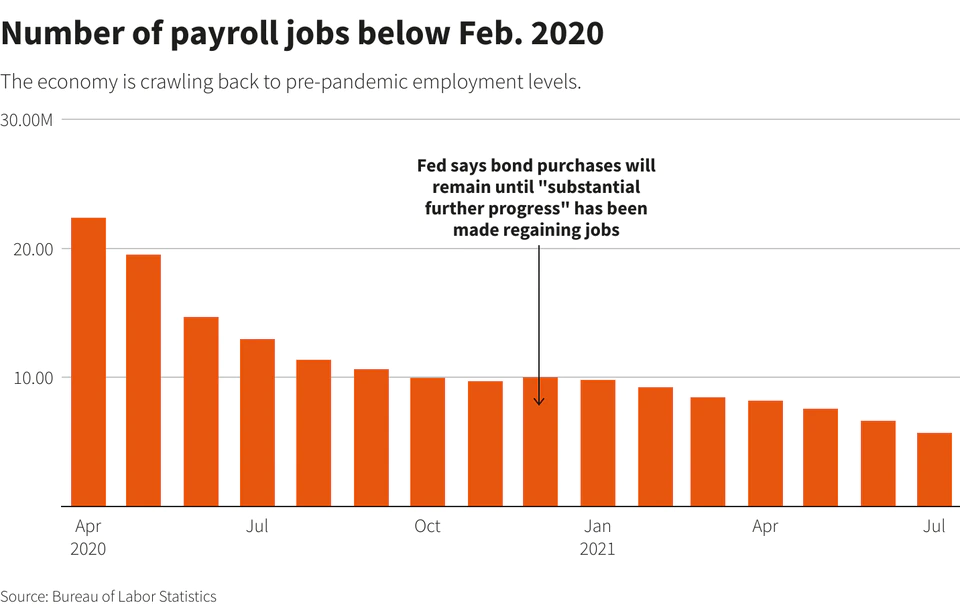

A gain of around 700,000 or more jobs in August would mean the U.S. economy will have reclaimed half of the 10 million jobs missing because of the pandemic as of last December, when the Fed promised it would continue its bond purchases until there had been "substantial further progress" in the recovery.

"That is the math that I am doing," Bostic said.

There are other calculations in the mix, including to what extent a surge in coronavirus cases fueled by the highly contagious Delta coronavirus variant hurts the economy.

Concerns about COVID-19 risks prompted the cancellation last week of the in-person portion of the Fed's Jackson Hole conference in Wyoming. It will be held on a virtual platform for the second year in a row.

The shift highlighted the risks the Fed faces as it plans its transition from emergency programs set in place in the spring of 2020 to policies needed to manage bursts of both economic growth and inflation more reminiscent of the 1970s.

Bostic said the rise and spread of the Delta variant had not changed his economic outlook in any fundamental way so far.

"What I have seen is some suggestion that things are slowing down, but they are still just slowing from extremely high levels. I have not seen big changes in the underlying dynamic," Bostic said.

Reporting by Howard Schneider Editing by Paul Simao.

_____

Source: Reuters